Home » Posts tagged 'Political Science'

Tag Archives: Political Science

The immaculate vibes of the Zombie Pandemic Simulation

A few weeks ago, my intro to IR class engaged in my favorite activity of the semester- the zombie pandemic simulation, and, as a great class session always does, it reignited my joy for teaching and learning. The vibes were, as the youth say, immaculate.

This assignment is adapted from International Relations Syllabus, United Nations Simulation and Rubric by Xiaoye She, with inspiration drawn also from Patricia Stapleton’s Politics of Plague course. I’ve run this simulation in person and online, at Kingsborough and at Doshisha University, and every semester, it is a huge amount of fun (which disguises the significant amount of learning that happens!). In my experience, running a simulation requires careful balancing- how can you simplify the incredibly complex real world institution (whether it’s the UN, as in this simulation, or the US Congress in my American Government class) enough that if fits into one class period while retaining enough of the specifics to make it a political science learning experience and not just a reasonably pleasant way to spend an hour and a half? What is the least amount of preparation that students need to do to be able to effectively participate (so that the largest number of students possible can participate)? For this simulation, I’ve settled on a country background and policy brief- maximum two pages total. (For students who show up, but didn’t prepare, they act as recorders and take notes; they are also able to participate in discussion but not vote, like the non-member states at the real UN).

If I may be permitted the use of a word I’m far too old to be using, it’s important to remember that the simulation is less about the specifics and more about the vibe. The UN is a fascinating organization, with specific procedures, bureaucracies, and protocols- it takes new diplomats and employees years to learn the ropes, so I can’t possibly expect students to learn every point of procedure in a one class simulation – that is not an appropriate yardstick. In an introductory class, the unit learning objective is to develop a general understanding of the functioning of the UN, as well as how the relative status of different countries affects what they are able to accomplish at the UN. I could give a lecture to communicate this general idea, sure, but I find that the active learning simulation generates a much deeper understanding- they get not just the words, but the essence, the vibe if you will, of the UN as a place for international conversation and collaboration.

Because it’s a simulation, the outcome is really up to the students- every one I have run has been different, but they’ve all been great! Highlights of the most recent simulation include a student doing a closer reading than I did of the assignment sheet (that I wrote!) to calculate the incubation period of Zombie-ism. Another student, representing a lower middle income country, offered to trade troops for financial assistance, which prompted a third student to comment that that seemed rather colonial (a throwback to our discussion early in the semester of critical IR theory and was a great opportunity for us to discuss that this “rich countries send money, poor countries send soldiers” is actually the way many multilateral peacekeeping operations function). Participation was active throughout the simulation for every student present (if you have taught a large synchronous online class, you will appreciate how rare and beautiful that is). Even students who are not poli sci majors, or are usually reluctant to participate in the class, were in it to win it.

It’s also been a great touchpoint for our discussions going forward for the remainder of the semester- the zombie simulation has come up in our modules on human rights, climate change, and transnational pandemics. Re-read the end of the chat from the simulation pictured above, and tell me you don’t dig these vibes

Open Ed Talk: Keeping the Person in Personalized Learning

On March 20, 2024, I gave a talk (rant?) about keeping the person in personalized learning. The slides can best be described as a collection of angry screenshots, so I won’t be sharing them, but in the off chance anyone is interested in the sources/information, here it is:

- D2L Personalized Learning

- Moodle Personalized Learning

- Blackboard/Anthology Personalized Learning

- Canvas/Instructure Personalized Learning

- Medcerts:

- 2hr Learning

- Eric Sheninger Personalized Learning with AI:

- Bernacki, M.L., Greene, M.J. & Lobczowski, N.G. A Systematic Review of Research on Personalized Learning: Personalized by Whom, to What, How, and for What Purpose(s)?. Educ Psychol Rev 33, 1675–1715 (2021).

- Data on Traditional/Nontraditional Students

- Robin DeRosa & Rajiv Jhangiani “Open Pedagogy” Open Pedagogy Notebook

- Maha Bali, “What is Open Pedagogy Anyway?”

- A chapter that explains my open pedagogy in excrutiating detail

- Reclaiming Personalized Learning: A Pedagogy for Restoring Equity and Humanity in Our Classrooms by Paul Emerich France

- Teaching Machines by Audrey Watters

Student Works I highlighted:

Turns Out I Love Selected Topics, or Geeking out Over Geeking Out

Classes are clicking along here- we’ve hit the midpoint of our stay in Japan, and of my courses. I have a medium-sized pile of midterm exams to grade, so what better time to write a blog post?

I continue to love all of my classes- IR because it’s my heart, Intro to US because the students absolutely slayed the Congressional Simulation (seriously, they were all amazing, and the Doshisha version of Markwayne Mullins and Elise Stefanik made me laugh out loud!), Human Rights because it’s a fascinating and challenging seminar that is pushing my brain in exciting ways, and Film because it is the most fun.

I expected the politics of film class to be the most fun for me- I got to pick several of my favorite movies and craft a list of my favorite international relations and comparative politics topics to discuss with students- what is not to love? These particular students are super sharp and engaging, which definitely helps, and their class presentations blew me away- Crazy Rich Asians and childhood poverty! Godzilla and bureaucratic politics! I hoped this class would be awesome, and it is certainly turning out that way.

I did not, however, anticipate how much fun selecting the topics in this “selected topics” style of course would be. I love teaching my introduction/survey classes- they are a good fit for students (the majority of whom are non-majors, taking the course to fulfill a requirement), so doing a general survey seems like the right move, not unlike (to torture a metaphor) getting students to eat and develop a taste for their vegetables before they jump into the dessert of more advanced political science . But this is not a survey course- we’re jumping around to the greatest hits, drawing themes to explore in data and theory from the films, and making different connections between and among each week’s topics. A very different approach than what I usually take in my intro to US and intro to IR classes (starting off with the Constitution and IR Theory respectively), because we need to eat our vegetables first. On my better days, I like to think I make the vegetables tasty, but skipping right to the most delicious stuff this semester has been so much fun! I mean, look at these slides- no one should be having as much fun as I am putting them together and then discussing them with a class.

And yet, here I am. And because Japanese university classes do not have an expectation that students will read before the class, it is not necessarily so very different from teaching a class to first year students who are new to political science. Somehow, we’ve managed to get into the guts of some complicated topics (gender pay gap, the history and evolution of the UN, bureaucratic politics) without building the base as I would in a survey course. It’s making me really excited to shake up my intro courses when I teach back in KCC next fall, to maybe incorporate a little more of the exciting juicy bits. Why not eat dessert along with our vegetables?

Weeks 3 and 4 Teaching

Two weeks that were so busy I didn’t blog, so here’s quick catch up of some highlights. The classroom continues to be a space of joy for me- I missed it so much, and I’m so glad to be back. It’s also very tiring, so I’m grateful that I will have my spring semester to finally finish the book I’ve been working(ish) on since 2015. I got speedily beaten at chess by one student while another (a former national master) looked on and tried not to laugh (I knew the outcome was a foregone conclusion, but we all had a good time). I also got to discuss feminist IR, the evolution of the US role in Asia-Pacific affairs, and graduate school with a graduate student, sitting outside at a picnic table on a sunny quad. I feel very lucky to be getting to enjoy academia and Doshisha.

As for teaching, Intro to IR and Intro to US are my bread and butter. I don’t need a lot of preparation for each week for these courses (that’s what teaching many sections every semester for many years will do for you- practice makes permanent!), but the courses continue to need minor tweaks to make them accessible to these students at this time. IR was extra fun, thanks to Victor Asal’s Realism Rock, Paper, Scissors and Prisoner’s Dilemma games (both of which are explained in this awesome article)- I think having some games to play gave us a chance to gel as a class, making discussion and asking questions a bit easier; it also kept me from talking too much. And I got to teach my favorite introduction to constructivism, where I show an image on the screen, and students write down their reactions, which we then share and compare. I use a photo of a gun, then a pile of candy (actually, it’s a photo of Untitled: Ross in LA which I reveal/we discuss after their reactions), and then a clown- they all have different reactions to each image, and it’s a great reference point for how meaning is constructed not objective.

Intro to American is a bigger challenge- it’s my class here with the largest amount of students (though still much less than I’m used to at home), and I’m trying to figure out how to incorporate more discussion/less of me talking. Streamlining what is usually 3-1 hour classes into one 1.5 hour class means prioritizing which content to cover, and has meant that some of the group activities I would ordinarily do have been reduced to links to articles for students to read if they are interested outside of class. In addition to adding translations to parts of some slides, I’m working on really thinking through what is absolutely most important, and what is the best way to convey it. I think this will help me refresh/update my approach back in the US as well.

In “Geeking Out” we moved on to Harry Potter, which made me nervous- a brand new class that I’ve never taught before and I did not have any material to really build on. But once I finally sat down and thought through what I wanted to do, boy was it fun! We did a large discussion of identity politics (excerpts from THE COMBAHEE RIVER COLLECTIVE STATEMENT in English and Japanese served as a fruitful jumping off point), and I again got to put together slides I am way too pleased with. I even used the cloak of invisibility as a metaphor for what identities were omitted from the films (subtlety has never been my strongsuit), and what that might mean (which segued into a great conversation about the lack of LGBTQ characters in the extensive Hogwarts universe, and how that may be connected to the author’s personal anti-trans stances.) Human rights in the potterverse is next up, and I’m extra excited (apologies in advance to the students in this class who have to deal with me geeking out so much).

For my human rights class, I adapted an exercise I use in my Introduction to IR class in the human rights section, which has students compare a list of rights with what is in the UDHR versus what is in the US Constitution. For this class, focusing explicitly on human rights in the US and Japan, I added in the Japanese Constitution. Despite the class having only two students (I’m still getting used to running a small seminar instead of the larger sections I’ve got more experience with, so it makes me nervous), the activity worked really well- great thoughts from the students, uncovering insights that helped us expand on the general human rights topics we’ve covered so far (the usual suspects in human rights: origins, definitions, universality, critiques, alternative frameworks); student observations included the vagueness of language and definitions, the time and political context of the writing of each document, the question of how older documents can apply to the 21st century world, negative and positive rights, and the different protections for economic, social, and cultural rights as opposed to civil and political rights. I’m hopeful that the experience of comparing the two countries for this assignment will help set the stage for the rest of the course, where we’ll look at more specific issues and the US and Japanese perspectives in greater detail.

Because I liked it so much, and because I’ve benefitted greatly from the work of others I’ve found on Twitter and APSA Educate, I’ve decided to make a version for sharing. You can get a copy of the worksheet on my website or directly here or on APSA Educate. I think it would be easy to adapt for a variety of courses- you could change the case study countries (or have different students do different countries!), change the rights being looked at, or change the human rights source document (ICCPR and ICESCR instead of/in addition to UDHR maybe?). I’ve done versions in person and online (synchronously), where we work for 8-10 minutes and then discuss, versions where students work as groups in person, and I’ve used it as a pure out-of-class/substitute-for-class assignment, with pretty positive results each time, so play around. If you use it, I’d love if you could let me know (mostly so that I can learn from your adaptation and improve for my own classes ;o)

APSA on Fire, or Why I’m Extra Weird at APSA

7 years ago, someone set several fires in the biggest hotel in Washington DC, causing a very difficult night for many political scientists, who had gathered for the annual meeting/end-of-summer-nerdfest of the American Political Science Association (APSA). I have long suspected APSA was the worst- a holiday weekend, right before school started in my neck of the woods, often overlapping with religious holidays for some folks- a terrible time to get away. It was always extremely hot, always very expensive (and never enough funding), and the coffee shops were always too crowded. Wars, hurricanes, and labor disputes have disrupted annual meetings before, and then someone started setting fires.

The APSA fire was not fun, but it was actually not the worst part of my weekend. When I finally made it home late the next day, I got the call that my dad died. Totally unrelated to the fire, hundreds of miles away, and yet these two events are forever connected for me. On the bright side, I had a full travel bag of summer season professional dark clothes already packed, so I was ready to hit the road again and do the whole “bury my dad thing” without any extra packing needed. On the less bright side, everything else. I can’t disassociate the two events. And since, as a tenure-track junior faculty member, I had to try to do APSA, I’ve been really weird at a bunch of them. If we’ve met at APSA, trust me when I say I’m usually not that weird (I’m still very, very strange, just not quite that weird).

In 2019, APSA returned to the scene of the crime, holding its meeting in DC again. I booked a room at the hotel that did not go on fire, had a panic attack in the Wardman Park exhibition hall (the last time I ever talked to my dad was when I called to tell my parents that a publisher was interested in my book proposal, and he yelled hello from the other room while I talked to my mom), and decided that probably going forward, APSA was not for me. I’d rather spend the money and time doing a writing retreat (okay, checking into a hotel with some awesome friends and writing during the day while taking breaks for fun, food, swimming in the pool, and hate-watching various HGTV-style shows- but what really is a writing retreat anyway?).

Ironically, 2020 decided that in person conferences were not for anyone, at least for a while. And APSA has finally moved the annual meeting later in the fall, so I won’t say I’ll never go again. I do miss the chance to connect with scholars and friends, see interesting research, and get inspired by my fellow political science nerds. But APSA is the reason I didn’t submit anything for this year; when I forced myself back to the exhibition hall before my last session in 2019 (to try to form new associations/work through my feelings) I chatted with a very nice lady from Fulbright about how they had a teaching-specific fellowship and had been trying to expand their outreach to scholars at community colleges. I think my dad would be proud (though if he were alive, the idea that I’m taking his granddaughters to a different continent would probably not be his favorite thing).

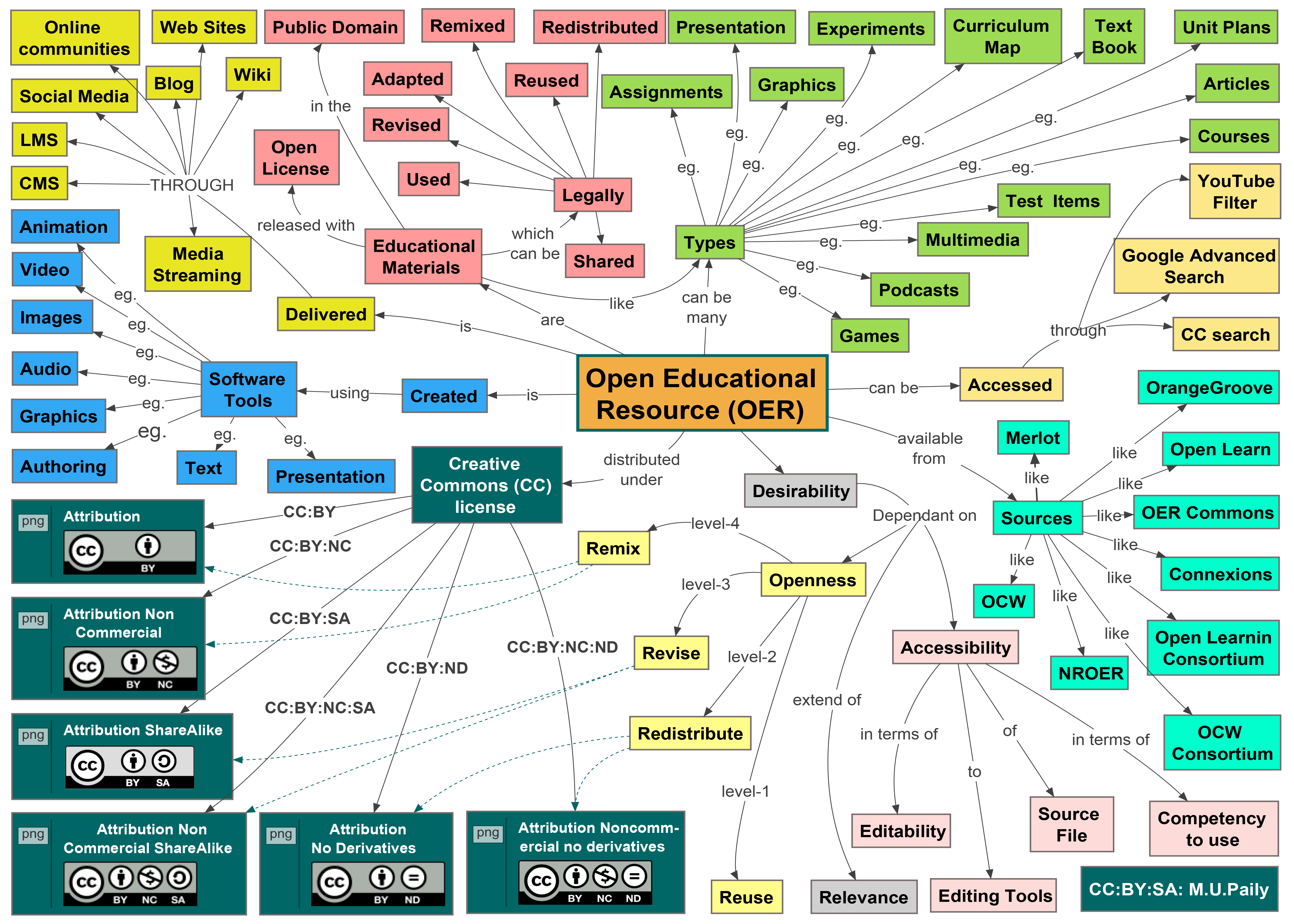

Open Educational Resources for Political Science

the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

So, I’ve gained a bit of reputation for myself as being an OER person for Political Science, which makes sense, because I’m constantly banging on about it to anyone who will listen- on Twitter, at conferences, on my campus, and now on this blog. I’ve been working on teaching with OER (Open Educational Resources) for 5 over five years now, and in that time, I’ve seriously fallen in love. It hasn’t always been smooth (the first OER I tried to author is so bad, I won’t even link to it, but you can read all about just how bad it was here), but it has led me to a much-needed (r)evolution of my approach to teaching, which is still ongoing. It’s made me a better researcher, too- I would likely not have stumbled into the worlds of Open Access and Open Data without exploring OER, nor would I have published research on it (it’s solidly half of my research agenda now). And that’s all in addition to the fact that I know my students all have zero-cost access to the materials they need to learn in my classes.

So I’m clearly hooked, and now it’s your turn. I’ll list my favorite resources for the courses I teach, as well as places you can find others. I’m only one person, and what I’ve found works for my specific approach to teaching my students at my institution. For reference, I teach introductory level classes with no prerequisites at a community college. Your mileage will certainly vary, so feel free to adapt to your own needs and preferences. Also, these are the courses I most frequently teach- I know there are loads more courses, so I’ve also included some places to look for more openly licensed materials.

For Introduction to American Government, which is the bulk of my teaching these days, the OpenStax textbook can’t be beat (in my opinion- but please note, I’m not an Americanist by training). For those interested in editing the text (which is perfectly allowed under the terms of its Creative Commons license), Openstax will be releasing all of their textbooks as google docs for easier editing in the fall. I will be offering students the option to edit the text, individually or collaboratively, for class credit starting next semester. I also use the Crash Course in US Government and Politics series on YouTube. While it is not an OER (since you can’t retain it or remix it), it is free for students to access, aligns really nicely with the topics I like to cover in the course, and is captioned and subtitled in a bunch of languages. I also have heard very good things about The Civics 101 Podcast, but have not taught with it myself.

For Introduction to International Relations, I really like the International Relations and International Relations Theory books from E-International Relations, paired with journal articles (some available openly, some through our library’s database subscriptions), and video and data from lots of different places. There’s a working outline of the materials here if you’re looking for a starting point for how a course might be laid out, but fair warning- it definitely needs work.

For both of these courses, I use the OER textbooks in a fairly traditional manner, because that works for me. Of course, since the texts are free, I could just as easily mix in selected chapters or papers from other sources. And there are plenty of places to find other sources, and plenty of material for courses besides the three I discuss here. There are reviews of several open political science textbooks at the Open Textbook Library, listings of fully open access journals and books at the Directory of Open Access Journals and the Directory of Open Access Books, 607 openly licensed Political Science books at The Open Research Library, 6 different Political Science courses at The Saylor Academy, and entire repositories to search through at OER Commons and MERLOT.

For Introduction to Comparative Politics, there isn’t a really great basic OER textbook (or at least there wasn’t the last time I taught the course), so I used library subscription resources, and made students comparativists- we did a draft of countries on the first day. When I get to teach it again, we’ll collect student cases into a book, which subsequent semesters of students will learn from, supplement, and revise.

It’s been a dream of mine to help coordinate an open comparative textbook, but so far, I’ve not found the time. More accurately, it’s a dream of mine that someone else will make a great open comparative textbook that I can just adopt. If anyone reading this teaches graduate foundational seminars in comparative politics and is looking for an excellent authentic assignment, having students make an openly licensed introductory textbook would be an awesome service to the discipline as well as a great way for graduate students to prepare both for their comprehensive exams and for teaching undergraduate students. If you don’t feel like publishing it yourself, the folks at Rebus Community offer a platform and model for collaborative book-building that could be adapted by a group of political scientists. E-IR also takes submissions.

The more of us that publish open access, whether our scholarly work or our teaching materials, the more that there is for others to adopt and adapt from. So the next time you’re preparing a course (or a scholarly article), I dare you to think open first. You’ll be surprised by what you might find, and where it might lead you.