I made a book!

On the fifth day of #OEWeek, I have a present for you!

But first, a very long story about how I came to be in possession of this present. 2 years ago, I saw a demo of this amazing platform for scholarly publishing, CUNY Manifold. And of course, I wanted to play with it right away because it looked amazing, and had really inspiring projects on it, but I hit little stumbling blocks that stopped me. Mainly, the one thing Manifold can’t ingest is PDFs, which are the one thing the books I use in my classes come in. Although that’s not really what stopped me- that was a relatively minor technical problem that I could have worked around, if my perpetual procrastination and permanent last-minute Sallyness did not always have me leaving class prep until the last minute. However, with the announcement that Openstax would be releasing Google Docs versions of their textbooks, and the switch to emergency distance learning due to COVID-19 that left me seeking ways to streamline the work for my students while increasing the possible ways for students to interact with our materials, I decided that I would finally sit down and get my POL 51 class materials set up on Manifold for the Spring 2021 semester (KCC has a very late start, which is also the reason I don’t usually plan any events for Open Education Week- it’s either the first week of classes or the last week before the first week of classes, and either way, faculty are not in the space to attend events at that time!)

So just in time for the end of Open Education Week, I am very proud to announce the launch of my American Government textbook on Manifold!!! I love this project, even though it is very much a rough start. The platform is extremely easy to use, and the documentation and help available are top-notch. The most time-intensive work was document preparation (not Manifold’s fault at all)- I had to stitch together individual chapter segments, and copy the alt-text descriptions from the online version of the book over, as the google docs provided did not have them. I even ended up doing the slightly-more-complicated-but-not-actually-that-hard YAML ingestion, so I could have individual chapters as links, and it really wasn’t that hard!! (I may have rejoiced loudly when I got it to work, but that says more about my limited coding skills than the difficulty of the platform). And now I have a very cool, streamlined, just-what-I-want book that is easy for students to access. I can’t wait for students to start using it! Some things I’m really excited about:

- I set up a private annotation group, so my class can share marginalia and hopefully get a little asynchronous discussion going on the text itself. This is available to anyone else who wants to use this too (even outside of CUNY)

- I can integrate additional resources, like the Crash Course American Government series I really like, right into the text where it is relevant. Previously, I linked the chapter and the videos to an outline on my syllabus, but now they’re right next to each other. (okay, so I’ve only go through Chapter 2, but it will all be finished soon!)

- I cut out the stuff that made the chapters seem extra long, but added them as resource cubes- Chapter Summary and Key Terms are now at the front of the chapter (which is how I tell my pressed-for-time students to use the book anyway)

- Manifold makes it very easy to share multiple versions of the text. While I hope many students will read the book online and annotate in our group, I know from past research and experience that some students will face bandwidth challenges, or prefer to print out their readings, so I stitched up a pdf of all of the chapters that students can download once and read offline.

I am extremely grateful to the nice folks at Openstax who sent me all of the chapters I requested. I even got extra lucky when I accidentally requested one I don’t usually use (the bureaucracy) instead of one I do (domestic policy). In going over the two chapters, I decided to keep the bureaucracy chapter, because I liked it more than I remember, and to use domestic policy as the basis for a new open pedagogy assignment/project/experiment- “Can you write a chapter in 2 sentences?” as I don’t love the way the topic is covered in the book, and I want to see what we as a class come up with.

I feel very full-circle at this moment, since the first open education project I did (before I knew what an OER was) was a (very bad) attempt at a book for American Government (How bad was it? I wrote an article about how bad it was). This one is SOOO much better and I couldn’t be happier about how OER have developed over time or about the progress I have made as an instructor.

But none of that is a present. The present is saving you the time of requesting and alt-texting these chapters from Openstax- download all of the word files here! You can download the files sent by openstax (individual chapter sections, without alt-text on images) or the chapters and supplementary pieces I stitched together, renumbered, and alt-texted. I can imagine lots of different ways to use these files- translation, editing, who knows what? So if you do use them, drop me line or a tweet, please! Also if you have any thoughts about my Manifold project, I’d love to hear them too- it is very much a work in progress.

What I Wish Someone Had Told Me About Scholarly Publishing, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Work Towards Open Access

My graduate training in scholarly publishing consisted of “You should publish stuff. It should be peer-reviewed.” Not exactly a full training in scholarly communication. Considering that doing and publishing scholarly research accounts for roughly one-third of my job responsibilities as a tenured associate professor, I wish they had spent more time on it, and maybe you already know about this (in which case, feel free to stop reading). But if you’ve never stopped to think about how the journal publishing sausage gets made, you may find this useful.

Rent-Seeking Behavior

As I’ve explored OER and open educational practices, I have been very fortunate to learn a bit about scholarly publishing models, and frankly, they’re a big-time scam. Or, if we wish to be social scientists about it, publishers of academic journals exhibit significant rent-seeking behavior: they seek to substantially increase their wealth without adding substantially to the value of the product or service they offer. Researchers, often funded by the public through grants or institutional support, do research, which they publish in scholarly journals for free (they also provide free labor as reviewers for journals). The scholarly journals are run by a few large publishing companies, five of which are responsible for half of all scholarly journal articles published in a given year. These companies run the journals, publish the articles which they got for free, and then charge libraries and the public exorbitant subscription fees (often in the form of “big deal” bundled databases) for access to the research articles, even if the articles were publicly-funded. Some institutions and funders have caught on to the irrationality of this system- locking up knowledge behind prohibitive paywalls seems wrong, holds back science, and cheats the public, who often has paid to support the research.

The movement towards Open Access is meant to remedy several of these problems. The NIH, the EU, and major research funders have begun to require grant outputs to be published openly (and include funds in grants for paying APCs). Faced with losing their source of free articles, publishers adapted, and were suddenly eager to offer open access options- they merely ask for authors to cover the cost of production that would have been covered by the fees they would have charged for access to the article: thus was the Article Publishing Charges (APC) born. APCs vary by company and journal, and are often upwards of $2,500. This reminds me of when traditional textbook publishers initially decried the quality and rigor of OER course materials, then suddenly switched to offering “inclusive access” courses that sneak course material charges into students’ fees without their knowledge or consent. In both cases, this isn’t surprising- profit seekers are going to seek profit.

The APC is How Much???

And they seeking it big-time. Nature Springer made waves with their announcement of going completely open, but as Dr. Julie Novkov pointed out this morning on Twitter, the devil is in the details: Nature Springer will charge APCs around $10,000 per article (with lower fees for scholars from lower income countries). And APCs are only one part of the equation- for previously published research, or research where scholars don’t have the funding for large APCs, much excellent research remains behind paywalls, which should more accurately be called pay-forts or pay-nuclear armaments, as the prices are far more prohibitive than a mere wall. The costs of library journal subscriptions rise steadily, while state and federal investment in higher education continues to fall. The COVID-19 pandemic is a dual crisis for library budgets- emergency moves to distance learning drastically increase the demand for electronic resources, while the economic impact on colleges and universities wreaks’ havoc on these institutions’ budgets.

So What Do We Do?

I need to point out that it is my institutional and geographic privilege that allowed me to remain ignorant of these problems for so long. As a researcher based in the US, database subscription rates are indexed to my country’s institutions budgetary level; in countries with smaller GDPs, open access fees are wildly out of sync with institutional and individual budgets, even when discounts are offered. Scholars in countries with lower GDPs are much more aware of the costs of publishing open journal articles. So it seems only right that I use that institutional and geographic privilege to work towards more equitable open access. Your position and privilege (full-time vs. adjunct, tenure-track vs. late career) will determine what you are able to do- but you likely can do something. I’m particularly talking to my tenured and promoted colleagues, who often have the most institutional power- they sit on the committees that write and decide on tenure and promotion guidelines and they help set the expectations in their departments and with their graduate students.

Scholars at all levels should learn more about Open Access- there is much more information than I’ve put here, and much better written, by people who know this stuff far better than I do (this article is a great start). Reach out to the scholarly communications librarian at your institution- they can inform you about what initiatives are already in place at your institution and point you towards resources for your own learning. Librarians are brilliant and amazing in general, and open librarians are extra awesome. Then get involved- share the information you’ve found with your colleagues who are not familiar with this rent-seeking behavior. Help dispel myths on your campus (no, not all OA journals are predatory, no APCs are not pay-to-publish). Publish openly if you can, preferably at truly open journals which don’t charge massive fees.

What if, like the UC system, more institutions banded together to reduce the fees charged by scholarly publishers, both at the APC end and at the subscription end? Many institutions are working on ways to make their scholars’ work more openly available, through institutional repositories and negotiations directly with publishers (here is information on the approach at Harvard, MIT, and the Europen Union Institute). The Registry of Open Access Repository Mandates and Policies (ROARMAP) maintains a database of hundreds of policies from funders and research organizations, including 834 universities/research institutions, so there are plenty of models to follow for those institutions who wish to explore their options.

More radically, what if we stop thinking about how to reform the existing journals and their profit-seeking corporate managers, and look at creating new journals? It seems like the services corporate journals provide (for which they charge exorbitant subscription fees) are the online review management systems, copyediting, and printing- what if scholars and their institutions decide to take over those responsibilities and start their own truly OA journals? It’s not the lark it sounds like- many truly OA journals already exist, and models could be adapted and innovated from. Yes, it would cost money and/or resources, but those could be creatively managed or repurposed as well? We’ve already largely moved past physical copies of journals, so printing expenses are negligible. Universities have websites- could they not spare server space for journals? Instead of contracting out copyediting, what if institutions funded graduate students as copy editors? Which would then give students experience in running open access journals- positive externalities! What if professional associations took back management of their journals and/or absorbed the cost of running them?

We Heat Our Classrooms

So, this summer, I’ve been thinking a lot about my course policies and my increasingly open pedagogy. I’m especially thinking about due dates (or their more ominous title “deadlines”) and flexibility. I wrote about how flexible deadlines helped students learn in my Spring 2020 classes here and I really don’t think I’ll ever go back to being the deadline hardass I was when I started teaching 15 years ago, when I really believed that strict course attendance and due date rules administered ruthlessly to all students regardless of anything else was the right way to run a class. I cringe when I think back on that, and to all of my former students, I’m really sorry. I’ve learned and grown, I promise.

There is, however, a strong pushback whenever I bring up flexible due dates, which I’ve done a lot this summer- I’ve discussed this with the excellent folks at APSA’s Online Teaching Workshop (sidebar for political scientists- go check out APSA Educate– the workshop contributed lots of resources, and there are many others that might be helpful), with colleagues in the KCC Open Pedagogy Fellowship, with other colleagues during other meetings, with folks on Twitter, basically with anyone I have talked to in the last 3 months. Many instructors who I really respect fall into the hard-liners category, often for the same reason- they say they enforce due dates because that’s what “the real world” will require, and they want to prepare students for their professional lives after graduation, or for the tougher 4 year colleges they will be transferring to after finishing on our campus.

I have several problems with this. First off, my students live every day in the real world. I don’t need to explain deadlines to them, because they already deal with hard due dates, like having to make rent, or not being able to- a 2010 survey of CUNY students found that 41.7% faced housing instability, and that was before the COVID-19 pandemic which has devastated the lives of so many New Yorkers as well as caused massive unemployment and economic slowdown which is likely to get much worse before it gets any better.

Furthermore, it would be downright hypocritical of me to demand on-time delivery of students work, because I am a habitual deadline blower! Like, seriously. I am late for everything- conference paper submissions, article reviews, returning exams, my own wedding.

Image from brightdrops.com/funny-life-quotes

And you know what has happened to me because of all this lateness? I’ve become a tenured professor of political science and a published author. The “real world” has not punished me too severely for my habitual lateness,* so why would I institute arbitrary punishment for my students? I think of it this way- there is hot and cold weather in the real world, but we don’t force ourselves to live in those conditions all day if we can help it. If it is cold outside, we turn on the heat in our offices, classrooms, and homes. If it is hot outside, we turn on the air conditioning. If we wouldn’t deny our students heat in our classrooms, in preparation for the cold outside, then we shouldn’t be excessively hardassed in preparation for the possibility that they will encounter hardasses in the future.

And everything I’ve been late on, I’ve had (what I believe to be) a good reason- I had other things to do, or care obligations, or I just forgot because life is busy sometimes. All of which apply to my students as much or more than they do to me- students have other classes, work and care obligations, and lead busy lives, without the privileges that come with being a tenured professor.

Due dates are important, and there are consequences to missing some of them, but what is the real consequence of a student submitting work late in my class? It may be slightly less convenient for me? Modified self-grading has really eased my grading burden significantly- I get to provide comments only, in conversation with students’ own self-grading reflections. I have heard some instructors offer different deadlines based on how much feedback students would like- the later they submit work, the less feedback they get, but the work is always accepted. Any inconvenience to me is far outweighed by the fact that I get to say, and really mean, that it is never too late to catch up in my class. If a student is willing to do the work, then I want them to do it, whether that’s in the schedule that I set up originally, or in the time that works best for them.

If you’re still not convinced, check out Kevin Gannon’s Radical Hope (well worth your time to read!) or if you’re pressed for time at the moment, Barrie Gelles’ recent blog post.

*Being late is still a jerk thing to do, and I’m honestly working on it. But I’ve had decades to improve, and am still not great at it, so extending the same flexibility to my students that I demand in my own professional life is the least I can do.

What Frozen 2 Taught Me About Open Pedagogy

We are a Frozen family. We have seen both films and all of the animated shorts. We have costumes, dolls, stickers, smaller dolls, coloring books, a gingerbread house- you name it. I’ve even gotten pretty good at Frozen-themed face paint. Between the leading ladies as the focus of the story, and my history as a high school musical geek, my love for this was practically pre-ordained, and luckily, my small associates and I love it about the same amount. We know every word to every song, and sing them loudly. Like I said, I’m a musical theatre geek, and there’s no way to hit some of those high notes without going all out!

So one day, when we were driving and singing along to the Frozen 2 soundtrack, my younger associate asked me to quiet down- she wanted to sing, and couldn’t hear herself over me. My pride extremely wounded, I tried my best to quiet down. It’s not easy- these songs beg to be sung out loud, and did I mention I’m a musical geek? But then I realized that when I sing more softly, I could hear my small associate’s sweet voice much better. And when I stopped singing all together, she got more confident, and got louder (and sounded adorable, but I’ll admit I’m biased). Which got me to thinking about voice and listening, and making space in my classroom. Like a blast of ice powers straight to my heart, my small associate hit upon the most important lesson (for me) of adopting more open pedagogy has been learning how to speak less, so my students have the space to speak more. Class should not be about me belting the greatest hits of American Government (as fun as that is for me) but in making the space for students to find their own voices and hits, which they can’t do if I’m talking the whole time.

Or in the words of another popular piece of streaming content on Disney +, talk less.

And yes, my associates are watching Frozen 2 as I typed this up. In the extremely unlikely event you haven’t seen it, you definitely should. If you have already, treat yourself to a second (or 32nd, no judgement) viewing. “You are the one you’ve been waiting for all of your life” and “do the next right thing” are absolutely necessary moods these days..

Happy New Year!

One of my favorite things about academia is we get extra New Years- every time a semester ends is an opportunity to reflect on how things went, and think about how to improve in the future. (my long winter & summer breaks mean I usually do this at the starts of things too. I like celebrating, don’t @ me).

So how did this very unusual semester of Spring 2020 go? I set out from the beginning, and reaffirmed when we switched to emergency distance learning, that I didn’t want to lose anyone- we would get through this together. On this measure, I was not wholly successful- in my early (9:10am!) class, 20 students dropped or never submitted even a single assignment, while in my 10:20am class there were 13 (incidentally, what a difference that early hour makes- attendance for our 5 in-person sessions before the emergency switch really helped lay the groundwork, and the earlier class was more sparsely attended then, so the difference is less surprising). Under ordinary circumstances, this would be not great, but given that New York has been and continues to be battered by COVID-19, which has been disproportionately dangerous to essential workers and ethnic and racial minority groups, which make up a large part of the students at my campus, I think we did as well as we could possibly have done. No student signed up for trying to juggle all of their courses online, possibly having to share devices with family that also needed to work or do school work from home, while facing economic strife, during a global pandemic. As I repeatedly told my students, my class is not your first priority and that’s okay.

And that’s one of the lessons I’ll take into next semester. In the fall, my students will be facing the psychological and economic fallout of the pandemic, and the likelihood of a resurgence is high. CUNY has yet to make a formal announcement for the fall, but my department has declared all of our classes online for Fall 2020, and I am really glad about this decision, because it seems like the only right one- my class is not worth anyone dying for. It’s not worth anyone getting really sick over, whether it’s a student, their family member, or someone they sit near on mass transit. That doesn’t mean I don’t think my class is important (I do!) or that my students’ education is not important (it really is!), it just means that it’s not worth dying for. In all of the discussions circulating in higher ed about whether to open, how to open, we need to open!!!, I think this is the big thing missing. I won’t try to argue that half-assed emergency distance learning is better than non-pandemic teaching. But NON-PANDEMIC TEACHING IS NOT AN OPTION RIGHT NOW!!! And it won’t be in the fall, either. So what changes to our classes can we make now to give us the best possible courses next term?

Things that worked extremely well for me this semester were flexible deadlines, students getting to choose their own assignments, modified self-grading and open-book unlimited-time tests. I’ll never go back to using closed-book or timed tests online- this reduced stress for students (essential during a pandemic, but a good goal during any time) and let them focus on learning, without me having to manage some surveillance technology or gatekeeping to control them. Our use of self-grading also reduced stress, because students were not as worried about their grade (since they were grading each assignment themselves), and the assignments were much better, because students were more familiar with the requirements of each assignment, since they had to assess themselves. Not only did students appreciate these things (I got many, many emails thanking me), it was actually much easier to manage administratively. I got to focus on giving useful feedback, not justifying the grades I assigned (since I didn’t assign them ;o). Whenever a student would send a worried email that they were going to be late, or needed more time, instead of wasting time demanding and verifying proof of their need, I got to quickly reply that they are the experts in what they need, and that the deadlines are flexible for this reason. Students who had problems at one or more points in the semester were able to catch up and complete their work- and isn’t that what we want, instead of nailing students on deadlines we impose? I also got to read really interesting projects, because students got to choose learning activities that were interesting to them, instead of slogging through what I required.

Of course, there are areas where I want to improve. I opted to go wholly asynchronous when we switched to distance learning, for practical and equity reasons. But I ended up missing the personal connection with students and we were never really able to develop a community of learners. Creating that sense of community is my main area for improvement in the fall. My campus is allowing us to indicate whether our fall classes will be synchronous or asynchronous, so I’m requesting synchronous (at least students will know what they are signing up for in advance), but I’m going to be a bit sneaky- each student will only be synchronous for 1 hour per week. I plan on dividing each class into 6 groups (or squads, or pods, or teams?), and I’ll meet with 2 groups during each class time- that way we’re never more than a group of 8 or 9, and we can actually talk with each other. This should hopefully balance the desire for facetime with limited device/bandwidth access, as well as give students dedicated time (the other 2 class hours) during the week to work on our class work (either individually or with their team). I’ll also tell each day’s group of two teams that if they can unanimously decide on a better hour to meet, we can move the session. I’ll encourage groups to develop their own norms and means of communicating, so they can help each other along (instead of having to depend on me). I’ll offer group versions of some assignment options, and most of our synchronous sessions will be planned/led by one of the groups.

Because of the emergency switch after the semester started, I offered students the option to blog in Blackboard (our LMS, which I hate) or on the CUNY Academic Commons (on our class site or their own). Most students opted for Blackboard, and I can’t say I blame them- it was already set up, and their other classes were likely using Blackboard too. But it’s a lost opportunity- knowing how to use Blackboard is only useful to use Blackboard- it’s not a transferable skill. Building out a website on the CUNY Academic Commons, however, means students have to figure out WordPress, which is a completely transferable skill that is actually not that hard to master. Next semester, I’ll require students to make their own sites which will contain all of their work for the semester (they’ll get to choose the sharing level of their site, as students have different preferences about privacy that must be respected). To support them, however, I’ll spend a chunk of this summer making how-to guides and videos for getting started, using as many different devices as I can find in my family (phone, laptop, tablet, etc), since I know students have different devices and bandwidths available. This will also ensure that I understand the fullness of what I’m asking them to do- i.e. I think it’s probably not that hard to run a WordPress site on a smartphone, but after this summer, I’ll know exactly how hard it is and how to do it, so I can help students who have trouble.

Finally, I am planning to change my slides. American Government is constantly changing, so I update them every semester, but these are really designed for use in-class. Without me guiding the class through them, they’re not that useful. Recording me going through them is extremely boring (not just for me- for any poor soul forced to listen or watch!)- there is a magic that happens in the classroom with these slides that doesn’t translate to online. So new slides are in order- I’m trying to think of ways to make them more self-guided and interactive, such as directing students out to data sources and government websites so they can play with them directly, instead of looking at the pieces I pulled in.

So that’s a lot for just one summer! And I’ve got a paper and a book to write, as well as some big family projects, so that’s a lot. On the brightside, we are committed to staying very close to home, so I’ve got some time. I’ll check back in as the summer progresses, and see how many of these words I’ll have to eat.

Open Educational Resources for Political Science

the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

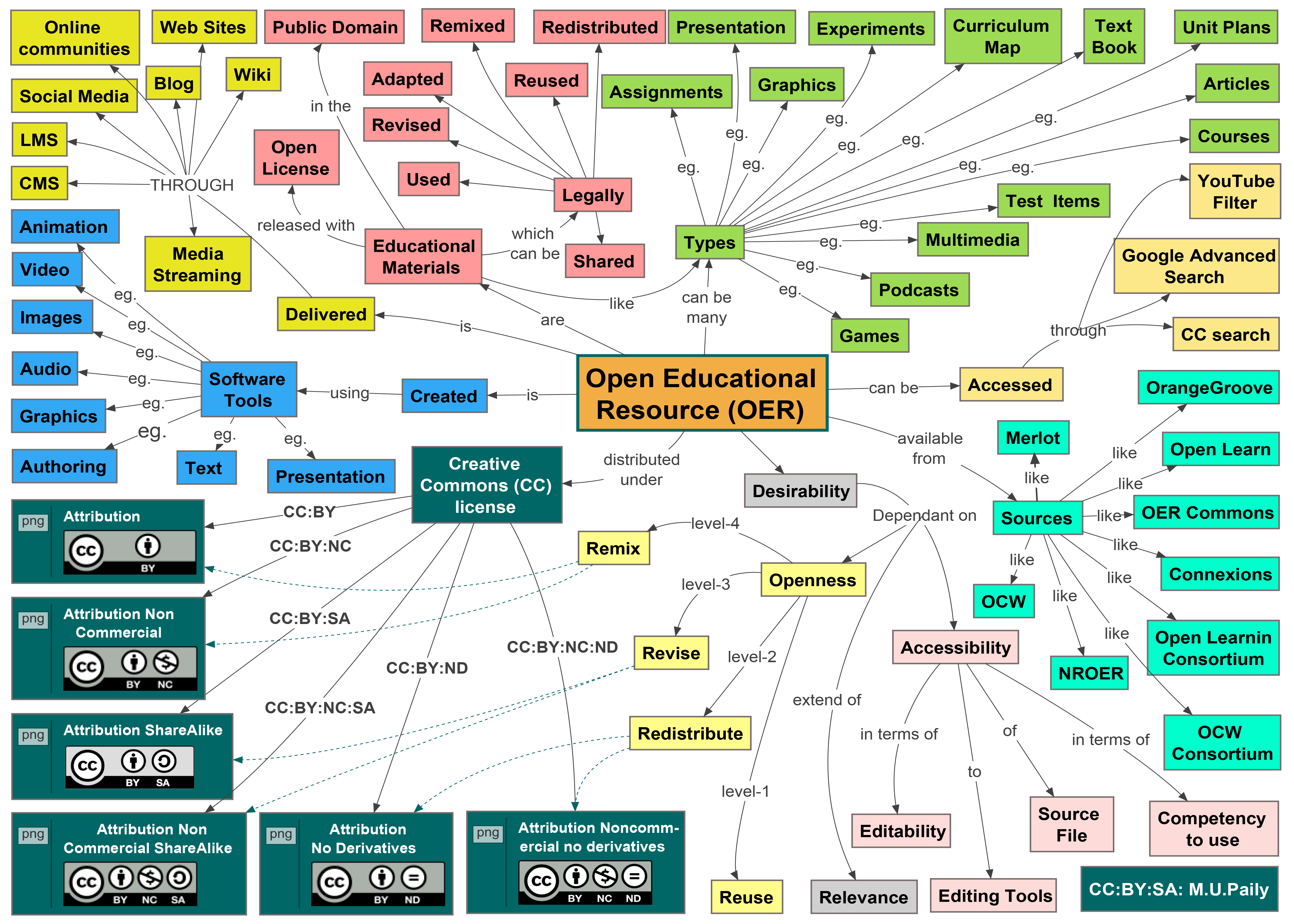

So, I’ve gained a bit of reputation for myself as being an OER person for Political Science, which makes sense, because I’m constantly banging on about it to anyone who will listen- on Twitter, at conferences, on my campus, and now on this blog. I’ve been working on teaching with OER (Open Educational Resources) for 5 over five years now, and in that time, I’ve seriously fallen in love. It hasn’t always been smooth (the first OER I tried to author is so bad, I won’t even link to it, but you can read all about just how bad it was here), but it has led me to a much-needed (r)evolution of my approach to teaching, which is still ongoing. It’s made me a better researcher, too- I would likely not have stumbled into the worlds of Open Access and Open Data without exploring OER, nor would I have published research on it (it’s solidly half of my research agenda now). And that’s all in addition to the fact that I know my students all have zero-cost access to the materials they need to learn in my classes.

So I’m clearly hooked, and now it’s your turn. I’ll list my favorite resources for the courses I teach, as well as places you can find others. I’m only one person, and what I’ve found works for my specific approach to teaching my students at my institution. For reference, I teach introductory level classes with no prerequisites at a community college. Your mileage will certainly vary, so feel free to adapt to your own needs and preferences. Also, these are the courses I most frequently teach- I know there are loads more courses, so I’ve also included some places to look for more openly licensed materials.

For Introduction to American Government, which is the bulk of my teaching these days, the OpenStax textbook can’t be beat (in my opinion- but please note, I’m not an Americanist by training). For those interested in editing the text (which is perfectly allowed under the terms of its Creative Commons license), Openstax will be releasing all of their textbooks as google docs for easier editing in the fall. I will be offering students the option to edit the text, individually or collaboratively, for class credit starting next semester. I also use the Crash Course in US Government and Politics series on YouTube. While it is not an OER (since you can’t retain it or remix it), it is free for students to access, aligns really nicely with the topics I like to cover in the course, and is captioned and subtitled in a bunch of languages. I also have heard very good things about The Civics 101 Podcast, but have not taught with it myself.

For Introduction to International Relations, I really like the International Relations and International Relations Theory books from E-International Relations, paired with journal articles (some available openly, some through our library’s database subscriptions), and video and data from lots of different places. There’s a working outline of the materials here if you’re looking for a starting point for how a course might be laid out, but fair warning- it definitely needs work.

For both of these courses, I use the OER textbooks in a fairly traditional manner, because that works for me. Of course, since the texts are free, I could just as easily mix in selected chapters or papers from other sources. And there are plenty of places to find other sources, and plenty of material for courses besides the three I discuss here. There are reviews of several open political science textbooks at the Open Textbook Library, listings of fully open access journals and books at the Directory of Open Access Journals and the Directory of Open Access Books, 607 openly licensed Political Science books at The Open Research Library, 6 different Political Science courses at The Saylor Academy, and entire repositories to search through at OER Commons and MERLOT.

For Introduction to Comparative Politics, there isn’t a really great basic OER textbook (or at least there wasn’t the last time I taught the course), so I used library subscription resources, and made students comparativists- we did a draft of countries on the first day. When I get to teach it again, we’ll collect student cases into a book, which subsequent semesters of students will learn from, supplement, and revise.

It’s been a dream of mine to help coordinate an open comparative textbook, but so far, I’ve not found the time. More accurately, it’s a dream of mine that someone else will make a great open comparative textbook that I can just adopt. If anyone reading this teaches graduate foundational seminars in comparative politics and is looking for an excellent authentic assignment, having students make an openly licensed introductory textbook would be an awesome service to the discipline as well as a great way for graduate students to prepare both for their comprehensive exams and for teaching undergraduate students. If you don’t feel like publishing it yourself, the folks at Rebus Community offer a platform and model for collaborative book-building that could be adapted by a group of political scientists. E-IR also takes submissions.

The more of us that publish open access, whether our scholarly work or our teaching materials, the more that there is for others to adopt and adapt from. So the next time you’re preparing a course (or a scholarly article), I dare you to think open first. You’ll be surprised by what you might find, and where it might lead you.

A partial list of what my students are dealing with

This semester, I have a very light (for my institution) teaching load because of other fellowships and work I’m doing- 2 classes of 40ish students each. We have a late start to our spring semester, so we had just shy of two weeks of face-to-face classes before the emergency pivot to distance learning. Sadly, I hadn’t really got to know the students too well (it takes time, at least for me), but I did try to lay the groundwork for building our little community based on care. I tried as much as I could in those 8 class sessions to convey that this class is meant for them, and that I would be there to help them along, in whatever way I could. Since the switchover to distance learning, I’ve tried in every communication with my students to emphasize that the assignments and due dates are all flexible, and that they should prioritize their health and well-being, and that of their families, over my class. I’d like to think that as a result of this care, students have felt more comfortable confiding in me what’s happening to them (although it could just as easily be the absolute desperation of the situation we’re all in now). Here, then, is a partial list of (anonymized!) situations facing the students in my class this semester:

-student A has several younger siblings, and they all have required synchronous learning for their schools, which means both that they need assistance and that there is not enough computer time or internet bandwidth to go around. (We talked about how it was an impossible situation, and brainstormed how to learn and do the work for the class using mostly their phone).

-student B does not have home internet and lives in an area where the free-for-COVID19 internet specials are not available (I offered to connect them to IT for the limited supply of internet-enabled tablets the campus has available for students, and outlined how to accomplish the class using only a smartphone and minimal data)

-student C was worried that not having a computer would make it difficult to complete their classes, and was very relieved when I relayed the link for how they could get one from campus. However, they couldn’t pick it up right away, as they had to wait for a ride- their parents did not want them riding mass transit to get to campus (whether this was due to the threat of germs or increased prevalence of hate crimes, the student did not say, but I said I’m sure it was the right move for them, and emphasized that due dates are flexible and assignments are self-graded)

-student D sent me a picture of their brand new baby! The baby was adorable, and I felt honored that the student would send me the photo. The photo was attached to an email saying that the student’s partner had just that day delivered a baby in a New York City hospital, and they were very nervous for obvious reasons, so their blog posts might be delayed this week (to which I responsed, forget about my class- make sure your newly expanded family gets home safely, get some sleep, & our class will be waiting for you when are ready). As I looked at the photo again, I noticed that the little card that goes in hospital baby trays, the one that notes name and date of birth, was prominently framed in the photo, and my heart broke for this student, realizing that the picture was not meant to share the joy of their new baby, but to provide proof that they were telling the truth. Because they assumed that their instructors would not believe them without evidence.

I’m not going to mention the number of emails from students who are sick, afraid they’re sick, caring for sick or high-risk family members, having to work, have lost their jobs, worried about money/food/housing, etc. because this post is already too long. And while I believe each of my students is unique in their own way, I am fairly certain their circumstances will be common to most, if not all of our students this semester. So please, please, please, be kind to your students. Give them the benefit of every doubt. As so many others have said about this already, be a human, and care for the humans on the other side of your screen.

Emergency Online: Thoughts and Resources for Quickly Adapting Your Course to Online

Last night, I went on a late night tweet storm about quickly converting your face-to-face course to an online course due to corona virus closures, so I thought I’d write it up here in case it would be useful to have it all in one place. Also Sean Michael Morris went on a much better one, so you really could just read that and stop reading here. University of Washington and Stanford have already closed their campuses, and it’s very likely more will follow. So what can you do, besides wash your hands, practice social distancing, and follow instructions from the CDC and your local authorities? Begin to prepare for the likelihood of moving your classes online.

To be clear, I’m not suggesting that anyone work while sick! I’m suggesting that now, while you’re not sick, is the time to think about and prepare an emergency plan for your classes, so that if you need it, you’ll have it. I’ve already signed up for Laurel Eckhouse’s Political Science Guest Lecture Volunteer spreadsheet which is awesome- if you’re in political science, sign up; if you’re not, consider starting one for your discipline.

And by the way, for everyone who does convert to a different modality, can I suggest keeping track of the work and time you invest? So that after the shock of the virus hopefully subsides, we can all work to advocate for proper recognition of and compensation for that labor, especially for the contingent and lowest paid among us, both retroactively and in institutional disaster preparedness planning in the future? How do we advocate in the future to ensure that all students have reliable home internet access?

In the more immediate term, give yourself, extend to students, and try to build into your class as you make adjustments to it, grace & flexibility. No one was expecting this when they built their syllabus or signed up for classes. It is serious and it is scary, so be patient with yourself and your students!!! How you manage your class virtually/online will vary widely, as all of our classes and teaching styles vary widely. Which they should- only you know yourself, your students, and your classes. I don’t think institutional band-aids- “we’ve created a course on Blackboard/Canvas/etc for you with everything you need- just grade it” will be very helpful, even if they’re available. Doing the same thing you do online that you did face to face does not work very well (in my experience), and also leaves a lot of advantages/affordances on the table. You are probably going to do things differently, so here are some resources that might help you think through what you might want to do in your own class. FYI, I am only recommending things that are not too technically difficult (gauged by “can I button mash/google my way through this?” which is my usual MO and good approach because, IT Support is likely to be stretched thin)

Consider groups (which can be done in your LMS or through google docs) for building liveness and community into virtual learning; it’s also a great way to make sure folks don’t get lost in a big crowd (similar to the way small discussion sections are used in large face-to-face lectures). If you spend time in your face to face class dissecting texts, check out Hypothes.is for social annotation (they’ve even added LMS integration. Try focusing on what you want students to DO- replace the time students would have been in class with time spent doing/making things- editing Wikipedia (Wiki Education can help you get started), writing content for the course (check out Open Anthology of Earlier American Literature and A Student’s Guide to Tropical Marine Biology for inspiration), blogging, making videos or podcasts or memes or powerpoint slidedecks.

My own thinking and approach on this stuff has been greatly influenced by exploring Open Educational Resources (#OER) and Open Pedagogy (#OpenPedagogy or #OpenEducationalPractices)- the more you can explore about this, the more you might find there are some upsides to teaching in the open and/or online. Some books (available freely online) to get you started and fired up: Open Pedagogy Notebook and An Urgency of Teachers. Get on Twitter and read up from Robin DeRosa, Rajiv Jhangiani, Jesse Stommel, Maha Bali, and Sean Michael Morris.

Finally, don’t think you have to make everything yourself. Look for things you can reuse or adapt- this not only saves you time but often results in better materials. I’ve tried recording my own lectures, but it took a long time, captioning was a pain, and honestly, they weren’t that good. For my Intro US classes, I find the Crash Course in US Government and Politics series on YouTube to be pretty great for the way I teach my classes; the videos are shorter than my lecture captures and far better produced (plus they’re captioned for accessibility and subtitlted in several languages as well).

Wash your hands and good luck.

Why I do What I do

These days, Open Education is one of the things that most excites me about my job- my work in open has made me an exponentially better teacher and a better scholar (open science & open access FTW!) and has given me the chance to work with faculty and librarians across CUNY and across the world. Open has been inspiring- open has given me new research questions, new ways to see the world and make connections between my research and the classroom, and new ways to think about what I really want to accomplish in the next phase of my career.

That said, it has also been tiring! There’s always something new or awesome to read or watch or research, people to talk to in person or electronically, all on top of my official teaching and research responsibilities. And on top of life and family. And this is true of everyone I know working on Open in CUNY (and in most places- is there anyone in higher ed these days who has too much time or funding? :o) Which is at least part of the reason that it took me so long to clean the 2019 data from the CUNY Zero Textbook Cost Student Opinion Survey. I’m going to share some basic analyses here to close out #OEWeek/#OpenEdWeek because it makes me so happy and I think we could all use some joy.

So far, we have 3606 (!!!) responses from 20 different campuses (!!!). A couple of us wrote a close analysis of the first semester of the data, and the main conclusions in that article are supported by the subsequent 3 semesters of data. The majority of student respondents believe they learn as well with digital materials as they do with a paper one, accessed their course materials in the first week of class or even before class started, and saw the zero cost as a major benefit of their course materials.

And this one is absolutely getting printed out and stuck to the wall of my office:

We asked this question figuring that students would only be willing to recommend zero-cost materials if they thought they were a good idea and the response is honestly going to keep me going for a long time. 97%!

There’s a lot more in the survey (including where students did their coursework, what devices they used, how much and why they printed, and what they thought the benefits and drawbacks are). This data has tremendous potential, and all of it is available at http://bit.ly/CUNYZTCSurvey. I can’t wait to see what some of you all do with it!

Finally, I can never adequately thank all of the students who shared their opinions in this survey, or the instructors across these 20 campuses who offered this survey to their students, or all of the OER coordinators on the campuses who sent the survey to the instructors, or all of the people across CUNY doing open education work, or all of the people around the world doing the work of open in so many different ways, but please know I APPRECIATE YOU.

Syllabus Experiments

used under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic License.

Every year, at the end of August and the end of February, I sit down to prepare my syllabi, planning out my classes and assignments, tailoring the schedule to each semester’s holidays/days off. When I was an undergraduate, I hated vague syllabi that never bothered to include the actual dates, just Week 1, Week 2, etc, so I’ve always taken the time to put in specific dates for classes, assignments, and exams. I usually teach several sections of the same classes- mostly Introduction to American Government, so my content didn’t necessarily change. It used to be that I would switch the days, make any little adjustments from what had worked well previously, and be done.

But a few years ago, I started really thinking about who was in my classes. The majority of college students, including those I now teach at a public community college, are classified as nontraditional (the fact that 74% of any population being classified as “nontraditional” is a big argument for another time), which means in addition to my class, they have a least some of the following to balance: other classes, part-time or full-time work, figuring out school after having been out for awhile, and/or caring responsibilities for children/siblings/parents. We’re a community college with no dorms, so everyone is commuting. When I started exploring OER a few years ago, I dug into specific institutional data about the students at my campus (which is on a beautiful beach in one of the most wonderful and expensive cities in the world), whereupon I learned that 66% of our students come from households with an annual income of less than $30,000. That’s about the time I started experimenting, a lot, with how I teach. I began to follow a lot of open educators on Twitter (@actualham, @thatpsychprof, @Bali_Maha, @Jessifer to start, and so many out from there) and got so inspired about the possibilities of teaching, if only I could let go of what I had always done and be a little brave about trying new things and opening up. First, I tried making my own book of original sources (you can read all about how badly that went here). Then I started using an OpenStax textbook for American Government and an e-IR textbook for International Relations. Began teaching on the CUNY Academic Commons. Starting experimenting with student blogging. Adopted a no attendance policy.

Now, each semester, I make changes. Some work well, and some are downright failures, but on the whole, opening up my teaching has been an awesome adventure. I was explaining to a colleague that none of this comes naturally to me (20 years of Catholic School leaves a lot of marks, and my disciplinary training was quite conservative as well)-, and he asked a logical question- why do I bother with it? And the answer was so simple I was surprised I hadn’t articulated even to myself before- what I was doing before didn’t work well for me, or for students. And a lot of these things seem to work much better. I’m so much happier with what I’m doing and how students are doing! So it’s worth the effort of switching things up.

This semester’s tweaks towards opening up my teaching: choose your own adventure and self-grading. I was really inspired by a presentation Benjamin Hass gave at the CUNY SUNY OER Showcase in 2019 about how they let their classes decide what their course will cover, and how students fill a notebook with their thoughts for their grade, which is determined solely by the amount of the notebook they filled. At the same time, I was reading a lot about ungrading. Arley Cruthers’ thread on planning a course and assignments with students sent me over the edge on this being the semester that I absolutely have to get more student choice involved, so instead of required assignments, I’ve got 13 options, worth a total of 150 points. Some require students to be in class, like our Congressional Simulation or the midterm and final exams, but most are meant to be done outside of class. Some are individual, some have the option to collaborate, and some compile individual contributions into a group collaboration. And there are two new ones for this semester that offer a lot of choice- a design your own option (have never done this- who knows if anyone will even want it?) and a book review. And the biggest change is expanding self-grading to all of the written assignments. I’ll include a short checklist of requirements with each assignment, and ask students to write a paragraph explaining how many points they assign themselves. If it works, it should alleviate grade-based anxiety and create better student learning. Who knows? If you’re curious about what we’ll be trying this semester, you can check out my teaching page.

And I just realized, I’ve inadvertantly (somewhat) COVID19-prepped my course! I already stopped awarding any points for attendance, and there are more than enough options/points that students can opt not to take the midterm/final exam (so if they feel like they are sick and need to stay home from class, they can, without worrying that they’ll miss something on the test). There’s also one option inspired by an assignment used by Dr. Brielle Harbin to cover one day of class for our collaborative note-taking document, so those who miss class can catch themselves up. If we get an official close-school order, I’ll make further adjustments, but as it stands, there is enough flexibility for students to make their own choices for what is best for them. Pedagogy of Care for the win, again.